Run Experiments Before You Write Code

The Lean Startup has a flaw. It’s a simple one.

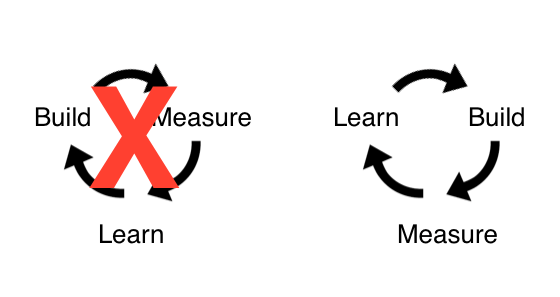

It advocates the feedback loop: Build -> Measure -> Learn. I agree wholeheartedly with this loop. The flaw is in where you should start.

I prefer: Learn -> Build -> Measure

It’s a subtle difference, but it’s an important one.

The Hidden Cost of Writing Code First

If you build first and then learn, you end up writing code that doesn’t matter.

Some of your experiments are going to fail. This means you are wasting engineering effort building features that don’t work.

That might work if you are an engineer or if you have an abundance of engineering resources.

But at most companies engineering is a scarce resource.

Even when engineering isn’t a scarce resource, building first introduces another problem.

What do you do when a feature doesn’t harm your metrics but it also doesn’t add value?

A good product manager would remove it. Less is more.

But this can be hard to do in practice.

You become attached to new features. Even when they offer little value. Even when nobody is using them.

It’s easy to convince yourself someone might use it someday.

Now the cost isn’t just engineering time, it’s also product complexity.

You have another feature that your customers need to learn, that needs to be integrated into the user experience, that marketing needs to promote, that engineers need to maintain.

We know that less is more. We’ve learned it over and over again.

But as we invest in our ideas, we become more committed to them. Even when they don’t work. This makes it hard to remove underperforming features.

The Counter-Intuitive Benefits of Acting as If You Have No Engineers

A better approach is to identify which features will deliver value before you build them.

Run your experiments before you write a line of code.

Act as if you have no engineers. If all you have is an idea, how might you know if that idea is worth pursuing?

If your goal is to test the idea itself, it might be hard to design an experiment without writing code.

But your idea is dependent upon a series of assumptions. You can test those assumptions without building the feature.

The more assumptions you test before building the feature, the more likely the feature will work when you do build it.

To get started ask yourself, “What assumptions have to be true in order for this idea to work?”

Suppose you are responsible for video integration in the Facebook newsfeed and you have an idea about auto-playing the video once the visitor scrolls to it. You could build this functionality and then user test it, but you would be better off examining your assumptions.

What has to be true for this idea to work?

- People want to watch the videos in their newsfeed.

- People want to watch the videos in their newsfeed right away.

- For people who don’t want to watch the videos in their newsfeed, it won’t be too much of a bother to stop an auto-playing video.

You might notice something about this list.

Assumptions are actually hypotheses in disguise.

You can test the first two assumptions by looking at your usage data. How many people play videos in their newsfeed? What percentage of their videos do they pay? How long after scrolling to the video do they push play?

Be sure to draw lines in the sand before you rush off looking for data. It will help to focus your data analysis and it will help to prevent bias.

If these assumptions hold to be true, you can move to the third assumption.

If you find that most people (say 80%) watch most videos right away, you might want to conclude that auto-play is a good idea. But you might want to first try to understand the use-cases where people aren’t watching video right away.

For example, if people aren’t watching videos right away because they are sneaking in a quick Facebook break during a boring meeting, auto-play might be disastrous.

If this is the case, the pain of auto-play for the 20% who don’t watch videos might outweigh the benefit for the 80% who do.

How might you find out why people aren’t watching videos right away? You could:

- Interview users and ask them when and where they use Facebook.

- Observe people using Facebook around you. How many are in a shared space without headphones?

- Survey people to understand their preferences on auto-playback.

- Conduct usability studies on a similar product that already includes auto-playback.

Notice how none of these options involve writing code. And yet they all help you collect data about whether or not your idea is worth pursuing.

This is what happens when you test assumptions instead of ideas. Ideas can be hard to test without writing code. But often you already have the data or can quickly design an experiment to test the underlying assumptions.

Surface your assumptions and do the work to test them before you write code.

Slow Down to Go Faster

This process is going to feel slow. Too slow.

You are going to get antsy. You are going to want to start writing code.

For any single idea, it’s going to feel faster to just build it. If it only takes a week of development, why would you spend a week or two experimenting before you build?

It doesn’t just cost a week or two of development.

It costs a lifetime of maintaining it.

It costs the learning curve for your customers to adopt the feature (or to ignore it).

It takes up pixels in your user interface.

And even when it doesn’t work, it’s going to be impossibly hard to remove.

But there’s a more important reason.

Expand your scope beyond one idea. Consider ten ideas. Should you build all of them?

Odds are only two or three are going to work.

Now you are building 7 or 8 features that won’t have an impact, that you’ll have to maintain, that will fill up your user interface, that will burden your customers.

It’s much better to run ten experiments before you write any code and only build the two or three ideas that actually worked.

Comments ()