How Does ChatGPT Work? A Guide for the Rest of Us

Everybody is buzzing about generative AI and there's a lot of jargon that comes along with it: tokens, embeddings, attention, neural networks, transformers.

Whether we are talking about ChatGPT, Claude, or Gemini, the large language models all work the same way. But understanding how they work can be a challenge.

Sure, you nod along in meetings. You skim the AI articles. You've probably even explained something about "large language models" to a family member.

But if someone asked you to explain what actually happens when you type a prompt into Claude or ChatGPT, what would you say?

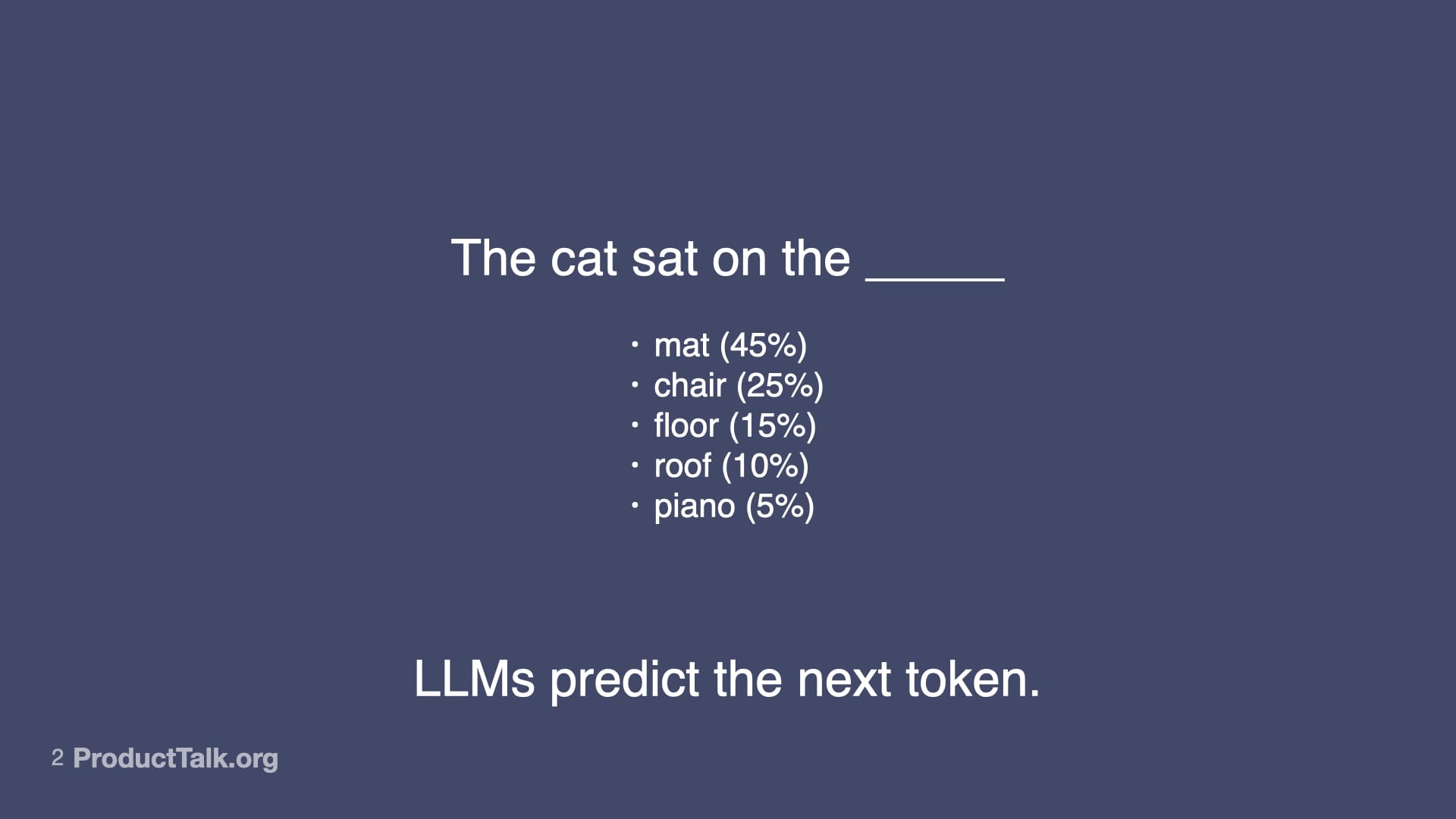

If you're like most tech-savvy people, you might say something like, "It predicts the next token." But do you know what that means or how it does it? That's where it gets interesting.

It can be challenging to understand how large language models really work. Many of the concepts can be genuinely hard to understand. Most explanations are either too technical or too hand-wavy. And it can be embarrassing to admit gaps in your knowledge.

But I think it's important to dive into how the technology works. Not only is it fun, but it can also help us better understand these models' strengths and weaknesses and how to use them effectively.

That's why I'm excited to share this guide with you. My goal is to start at the beginning and walk you through exactly how a large language model works. No machine learning or engineering background required. We might do a little arithmetic and multiplication, but I promise to keep it simple.

My goal is to help you understand the jargon and know how it all fits together to produce the magic that we experience when using these models every day.

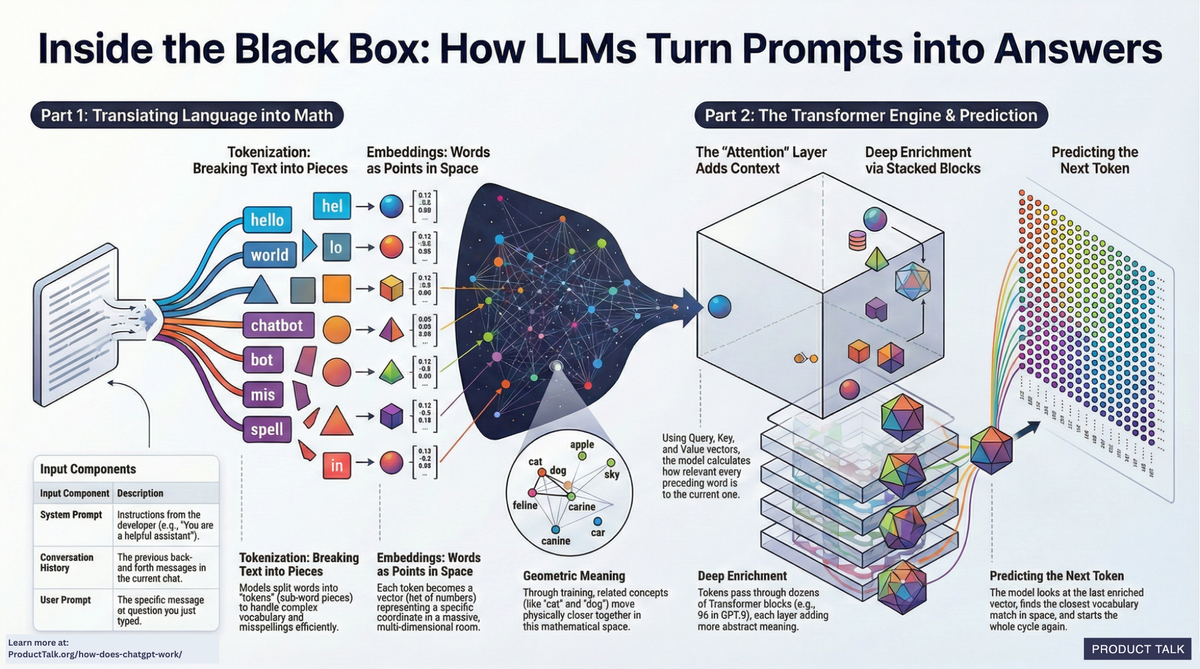

Start with this high-level overview generated by NotebookLM and then dive deep into the article below.

🎖️ This Product Talk Article is brought to you by Story-Based Customer Interviews. Collect reliable feedback from every customer interview. Conduct practice interviews and get detailed, personalized feedback from our AI Interview Coach. Invest in your interviewing habit today.

🎖️ This Product Talk Article is brought to you by Just Now Possible, a podcast about how AI products come to life—straight from the builders. If you are being asked to add AI features to your roadmap, you don't have to start from scratch. Get a head start by hearing how other teams are navigating similar challenges. Find it on YouTube, Apple Podcasts, and Spotify.

What You Already Know

If you use ChatGPT, Claude, or Gemini, you already know the basics—you type in a message, the model does something, and you get a response.

Input → Black Box → Output

In this article, we'll cover all three parts:

- Part 1: The Input: How your prompt becomes something the model can work with

- Part 2: The Black Box: What actually happens inside

- Part 3: The Output: How the response you see is generated

Let's start with the input.

Part 1: The Input

It might surprise you to learn that the message you type into an LLM (often called the prompt) isn't the only thing that is sent through the black box. Each chat interface (e.g. ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini) adds a system prompt to every message.

Input = system prompt + user prompt

If you are using a chat interface where you are chatting back and forth with the model, the input also includes the full chat history.

Input = system prompt + conversation history + user prompt

Application developers also add system prompts to the input. This is why you can type the same prompt into Claude Code and into Cursor (another AI coding tool) with Claude as the selected model and still get different output. Cursor's system prompt is different from Claude Code's system prompt.

Claude Code, for example, includes your Claude.md files in the system prompt. It also includes what tools are available, what skills are enabled, and so forth.

Before the model can do anything with the input, it needs to convert your text into something it can process. This happens in two steps: tokenization and embedding.

What Are Tokens and Why Do LLMs Use Them?

Large language models don't read or predict words. They read and predict tokens.

A token is usually a piece of a word—what linguists call a subword. The word "tokenization" might become two tokens: "token" and "ization." Common words like "the" or "cat" are usually single tokens. Rare or long words get split into multiple pieces.

Why does it work this way?

Building a vocabulary of every known word—in every language—would be a giant undertaking, especially if it also had to include misspellings and domain jargon. This would be impossible to maintain. And the vocabulary would still be limited. The model wouldn't be able to understand any word that wasn't in the vocabulary.

Tokens solve this. A vocabulary of 50,000–100,000 tokens can represent virtually any text by combining pieces. The model can recognize new words and even misspellings because it processes them as a series of tokens.

Every model has a context window size that's measured in tokens. This is the maximum amount of input that a model can work with at once. For example, Claude has a 200,000 token context window. Gemini has a one million token context window.

So the first thing that happens to the input is it gets tokenized—converted from words to tokens. Next, each token is turned into an embedding vector. If you aren't familiar with embedding vectors, don't worry, we are going to cover that right now.

Embeddings Are Tokens Represented as Points in Space

Once your text is split into tokens, each token gets converted into a vector—a list of numbers. These vectors are called embeddings.

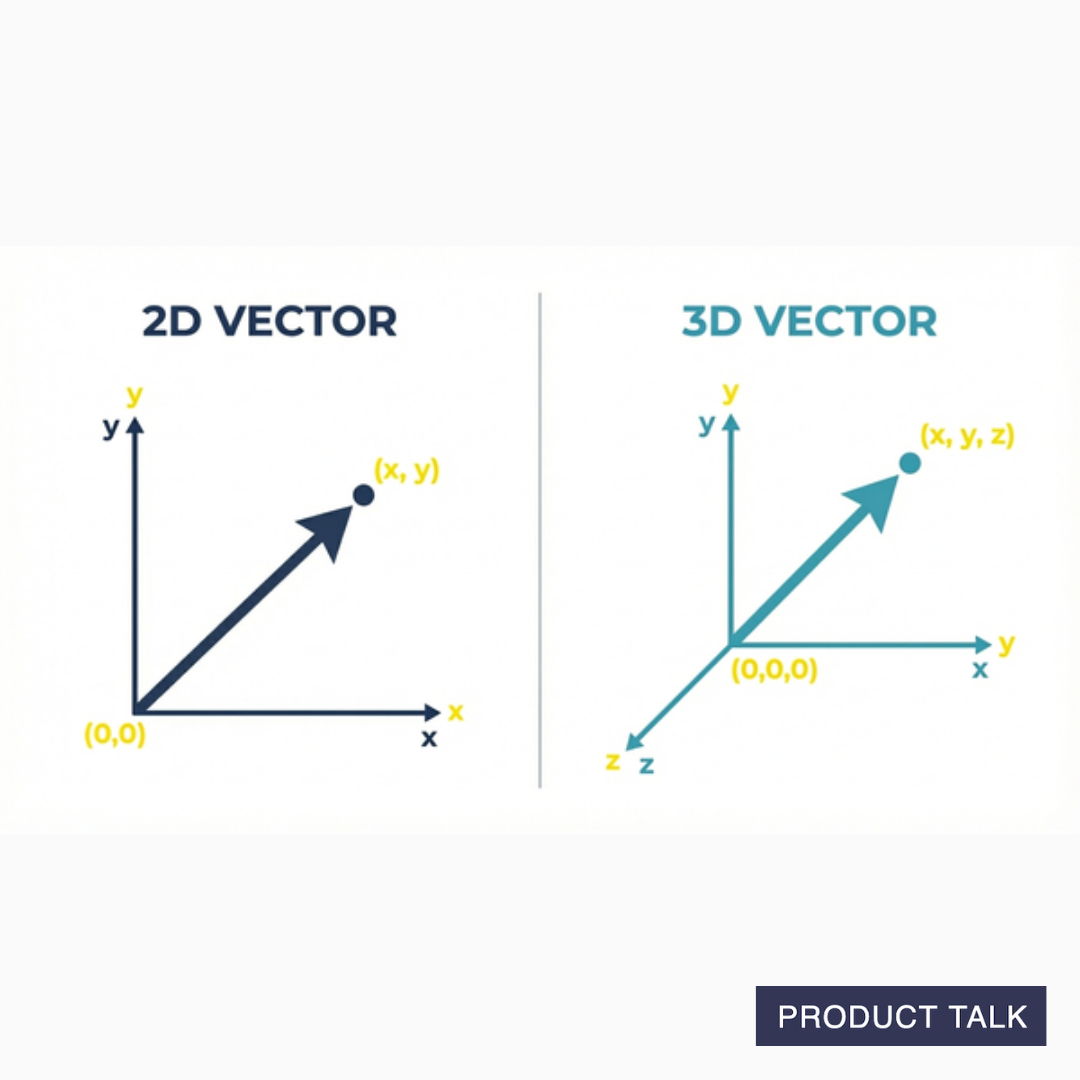

If you don't remember how vectors work (I didn't), let's do a quick refresh. A vector describes a magnitude and a direction. It's an arrow.

You are probably familiar with a point (x, y) in two-dimensional space or even a point (x, y, z) in three-dimensional space. A vector in two-dimensional space (x, y) would be an arrow drawn from (0,0) to (x, y). A vector in three-dimensional space (x, y, z) would be an arrow drawn from (0,0,0) to (x, y, z).

In large language models, an embedding vector is an arrow in n-dimensional space, where n is in the thousands. Don't worry, I can't wrap my head around that either.

But just like (x, y, z) represents an arrow in three-dimensional space, an embedding vector—a list of thousands of numbers—represents an arrow in n-dimensional space.

For our purposes, it's easier to think about a vector as a point rather than an arrow. The point is the tip of the arrow.

Imagine a massive room with thousands of dimensions (impossible to visualize, I know). Every token in the vocabulary has a specific location in this room. The embedding vector describes this location. And here's what makes it powerful—similar tokens are close together.

"Cat" and "dog" are near each other—they're both pets, both animals, both appear in similar sentences. "Cat" and "spreadsheet" are further apart—they have little in common.

At the start of training, these locations are random. "Cat" might be next to "democracy" by chance. But as the model trains on billions of examples, tokens that appear in similar contexts gradually move closer together. By the end, the geometry of this space captures something meaningful about language.

The model vocabulary maintains a mapping between tokens and their corresponding points in space—their embedding vectors. Each token in the input is replaced with its corresponding embedding vector. You can think about it as your tokens being located in the giant room.

This spatial arrangement isn't just a nice metaphor—it's how the model actually works. When the model generates output, it's literally finding the point in this space closest to what should come next, then mapping that point back to a token.

Why do we need such a big space? The bigger the room, the more information we can capture—the more nuance we can distinguish between words. If the room was small, all the words (even unrelated words) would be jumbled together. By using a really large room, there's plenty of space to represent all the nuanced relationships between different words.

Part 2: The Black Box

Once the input is tokenized and converted to embeddings, they are sent through the black box—the model.

To reveal what's in the black box, we have to start with a little history. You've probably heard of machine learning and neural networks. And you probably know that they predate large language models.

We use neural networks to help solve a wide variety of problems. We use them to cluster similar things together, to drive recommendation systems, to classify things, and even to optimize things. But this technology didn't unlock anything like what we see today with large language models.

To understand how large language models work, we have to first understand neural networks, what they do well, and how they are limited. And then we'll look at what was introduced that unlocked the power of the large language models we use today.

What is a Neural Network?

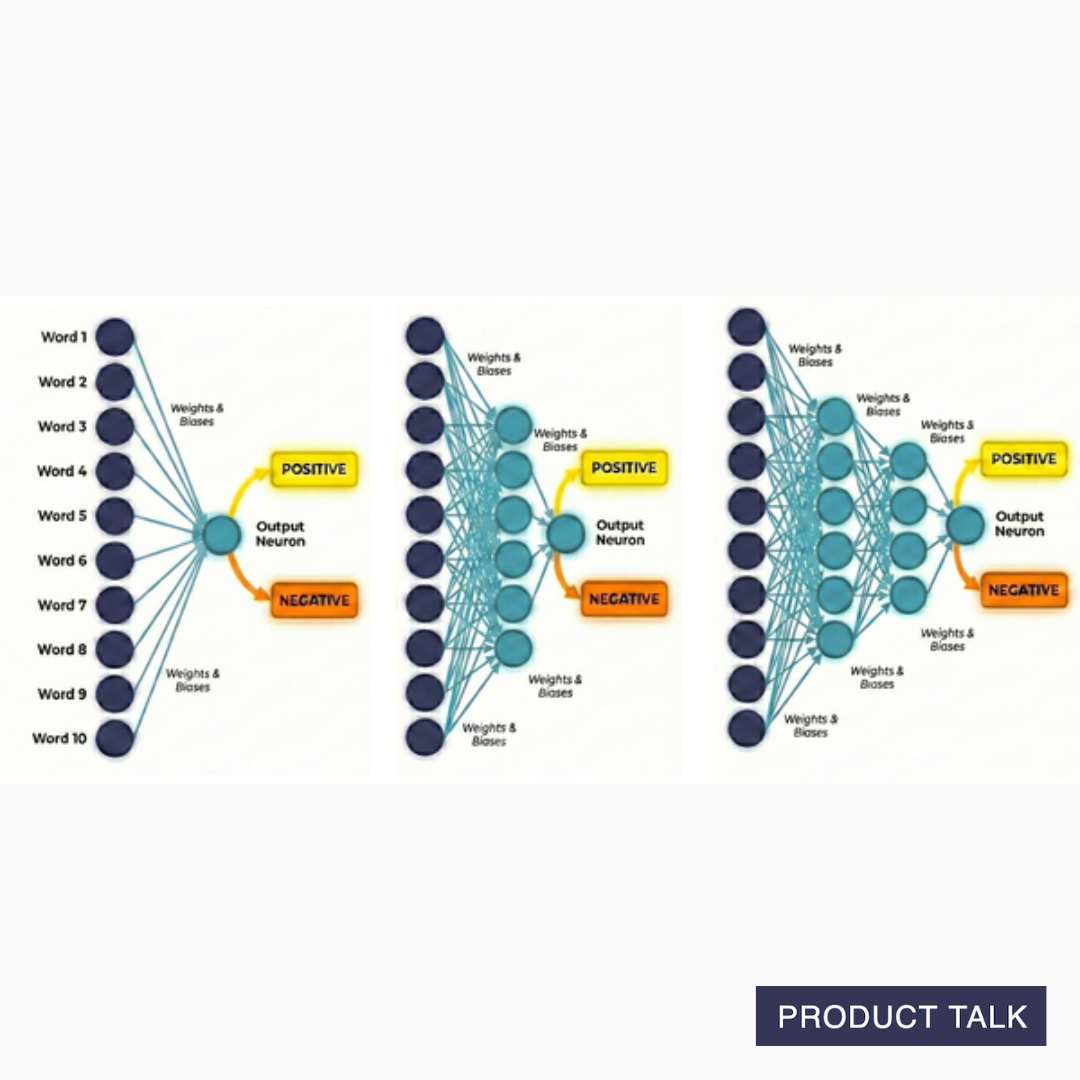

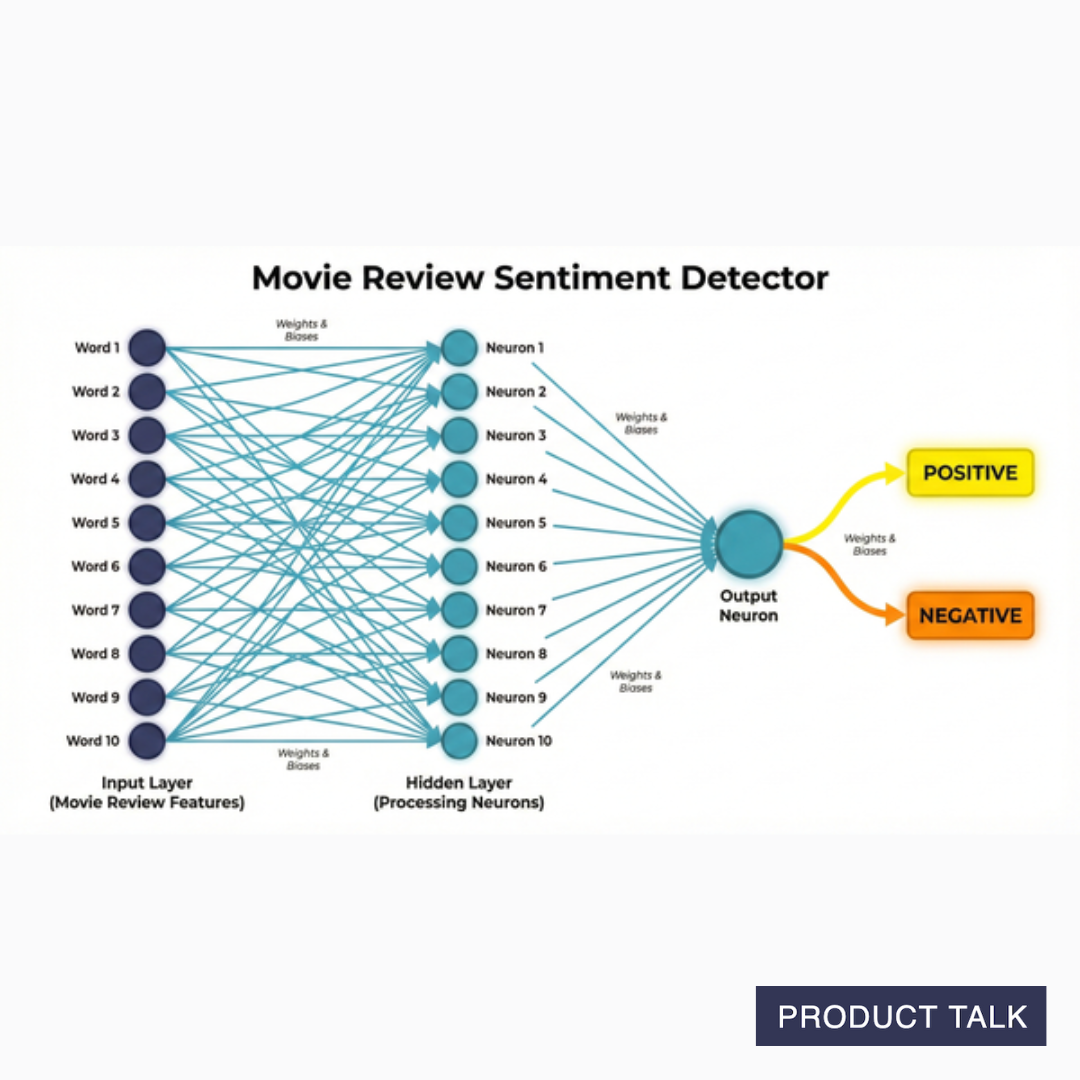

Imagine you want to build a system that can predict whether a movie review is positive or negative. A neural network would be a good strategy for building this classification system.

A neural network also takes an input, processes it like a black box, and outputs a response.

Input -> Neural Network -> Output

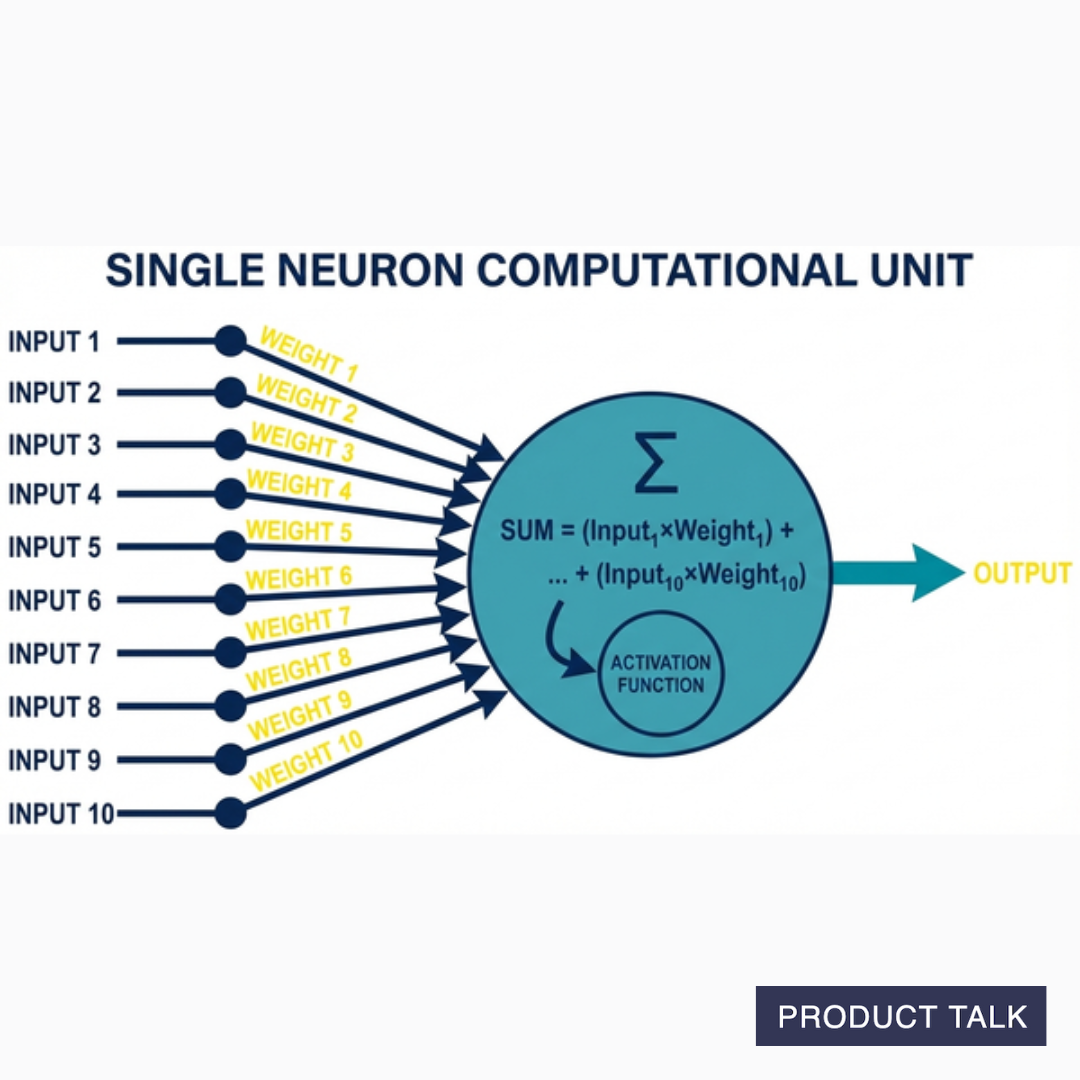

A neural network is made up of neurons. A neuron is a computational unit that takes a set of inputs, multiplies each input by a corresponding weight, sums those products, passes it through an activation function, and produces an output.

A neuron's number of weights needs to match its input. So if it's designed to take ten different inputs, then it needs to have ten weights.

The activation function is a little complex. It transforms the weighted sum in a non-linear way. You don't need to understand the math here. The key idea is the activation function determines how much signal is outputted.

In a neural network, multiple neurons can be stacked in a layer and many layers can be stacked on top of each other. The more complex the network, the more complexity the neural network can manage.

To build our movie review sentiment analyzer, we would need to define our starting vocabulary. Since we are only looking at sentiment, we don't care about every word in a review. Instead, we might create a vocabulary of 1,000 sentiment-related words.

This means our neural network would take in 1,000 inputs—each word in our vocabulary with a count of how often they appeared in the review.

Our network would need to have two layers of neurons. The first layer might have 100 neurons. Each neuron in that network would take in 1,000 inputs and multiply each by its corresponding weight. This means each neuron would have 1,000 weights. The output of each neuron would be the sum of each of those multiplications.

The second layer of our network might just be one neuron with 100 weights—1 per neuron in the first layer. It takes in the weighted sums of the first layer, multiplies each by its own weights, and outputs a final score: positive or negative.

The only math you need for understanding at the conceptual level how a neural network works is multiplication and addition. Numerical inputs get multiplied by weights, then summed, to produce the output.

But how does this actually work? How do the weights represent anything meaningful? How can we enter word counts and get out a sentiment?

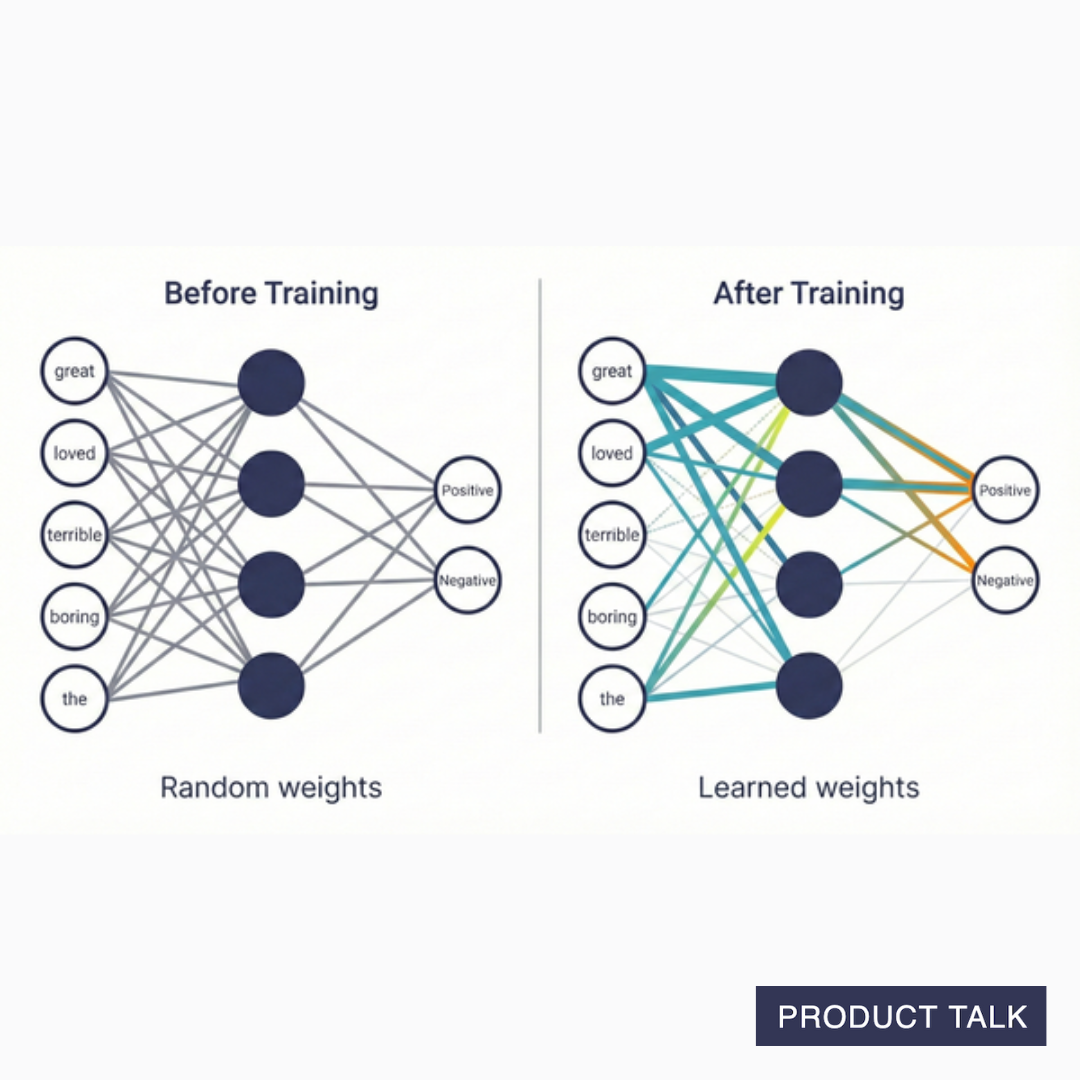

This is where training comes in. To start, our weights across the network are random. To train the network, we would need a large set of movie reviews that are labeled positive or negative.

In training, we would feed each labeled review into the network and get out a prediction (positive or negative). In early training rounds, we would get a lot of wrong answers. The weights don't carry any meaning yet.

Weights capture meaning through training. As we feed labeled reviews into the neural network, the model adjusts its weights based on whether it got the right or wrong answer.

Answers aren't just binary, e.g. positive or negative. The prediction is based on a likelihood—a confidence score. So the output is more like 80% confidence it's positive. In the event of a wrong answer, the model will adjust its weights to be less wrong. Even in the event of a right answer, the model might still adjust its weights to increase the confidence score.

Why "less wrong"? The model can't just change its weights to get the right answer because this might cause problems for other inputs. Instead, as the model trains, it nudges all the weights toward less wrong answers—the result is more correct answers on average.

After enough adjustments, the network has learned patterns. We might find that neurons respond strongly to words like "great" and "loved" for positive predictions, and "terrible" and "boring" for negative ones. But we never told it this—it discovered these patterns from the data.

I learned about neural networks in college. I even had to program one. But it still blows my mind that a network that starts with random weights can—through training—turn into a black box that produces meaningful outputs. This is a key idea that everything else will build upon.

The Key Limitation of Neural Networks

Our sentiment example works surprisingly well for simple cases. But what happens when a movie review contains the sentence "This movie was not great"?

We are simply feeding in a list of words with their frequencies. The word "great" gets counted the same as if it was in the sentence "This movie was great."

The neurons consider each word in isolation. There's no interaction or communication between the inputs. The neuron can't see that it has both "great" and "not" in its input and know to treat "great" differently.

Before transformers, researchers tried several different techniques to help neural networks get better at understanding language. But none of them worked that well.

Then came the breakthrough.

Attention Is All You Need

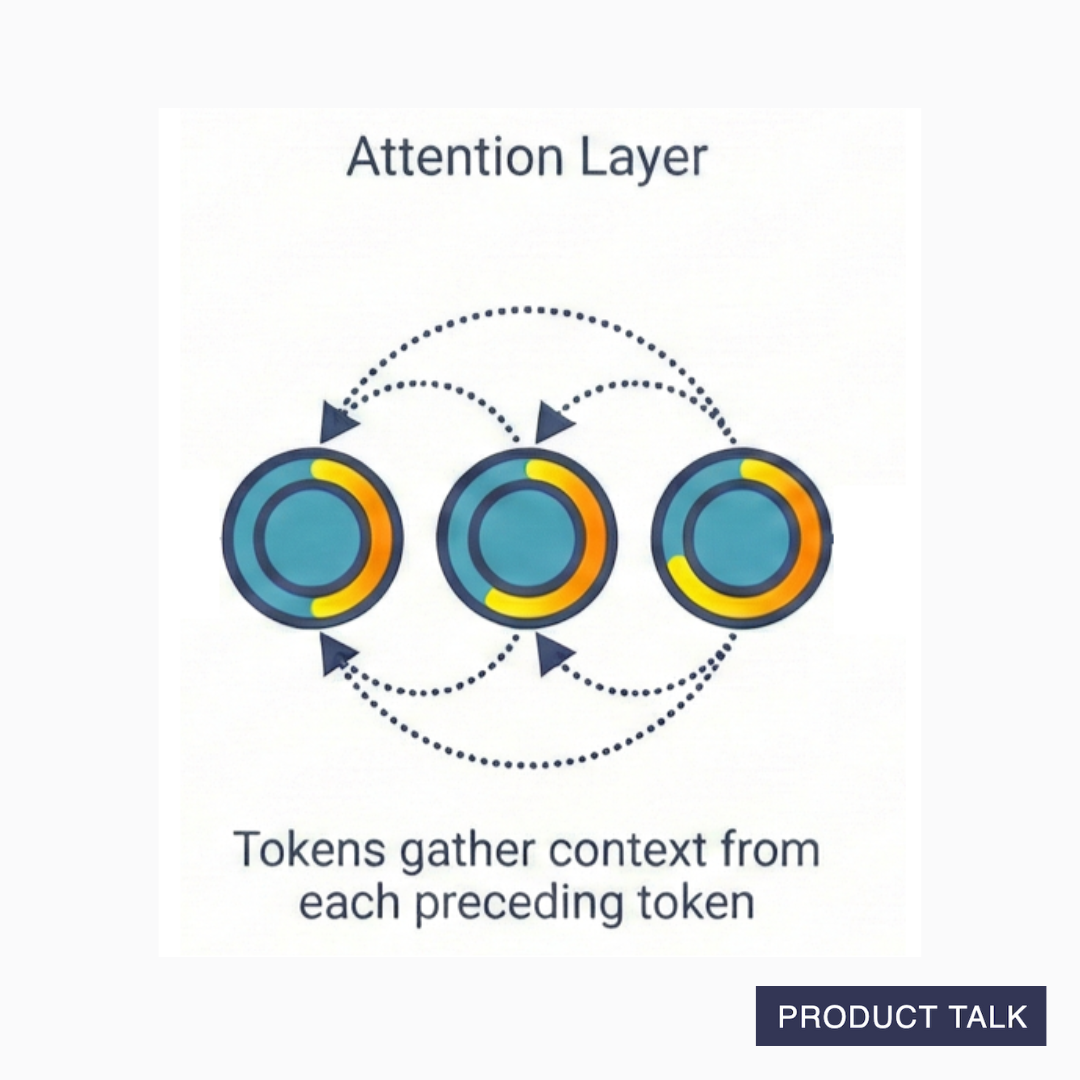

In 2017, researchers introduced a paper called "Attention Is All You Need." The core idea is to modify the embedding for each input token based on the context in which it occurs before it goes through the neural network.

In a large language model, the input is tokenized and converted to embeddings (points in space), but before it's sent to a neural network, the embeddings are sent through an attention layer. The attention layer adjusts each token embedding with information about the tokens that preceded it.

The embedding for "great" when it appears in the context of "This movie was great" will look different from the embedding for "great" when it appears in the context of "This movie was not great." In other words, the first "great" will be located at a different point in space than the second "great."

Instead of "great" living in one location in our giant room, it lives in many different locations depending on how it's being used. The attention layer helps the model understand which version of "great" is being used. You can see why the room has to be so big. Every token has many locations based on the context in which it appears.

After the attention layer, our adjusted token embeddings are sent through a traditional neural network. There's nothing special about this neural network. Each neuron still works with each input in isolation. But because each input has context built in—our two "greats" are represented differently—the neural network can learn context.

Now that you know the big idea behind attention, let's get into the details of how attention works in practice.

How Attention Works: Understanding Query, Key, and Value Vectors

It took me a while to really understand the mechanisms for how attention works. But I'm glad I took the time to work through it. It's an elegant solution for a hard problem. To understand it, we are going to have to get into some math. But I promise to keep it simple and walk you through it step by step.

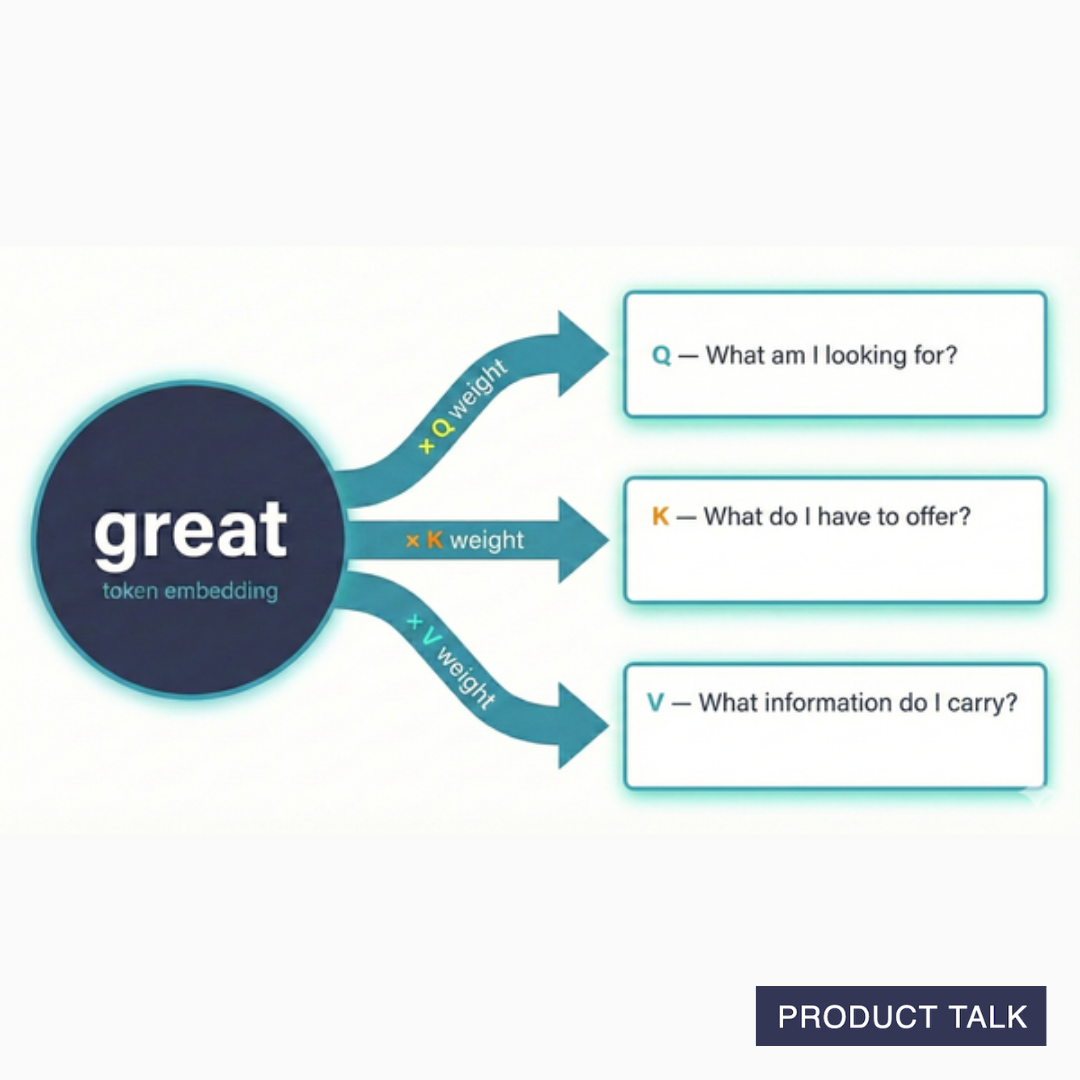

In the attention layer, each token embedding gets transformed into three new vectors—Q, K, and V vectors. To generate these vectors, the token embedding vector is multiplied by a weight for Q, a weight for K, and a weight for V.

Remember, in a neural network, neurons take in inputs, multiply those inputs by weights, and then sum the outputs. Through training, those weights start to represent meaning. In our movie example, "great" gets associated with a positive review.

The attention layer relies on a similar idea. It doesn't use neurons. But it does use weights. Each token's embedding gets multiplied by the same Q-weight, K-weight, and V-weight. Through training, these weights start to capture meaning.

When we multiply a token by all three weights, we get three vectors that adopt specific meanings:

- Query (Q): "What is this token looking for?"

- Key (K): "What does this token have to offer?"

- Value (V): "What information does this token carry?"

Think of it like a search system. The Query is the token's search term. The Key acts like a title for the information the token carries. The Value is the actual content of the token.

The goal of the attention layer is to add context to each token embedding. We want "great" in the context of "This movie was great" to be meaningfully different from "great" in the context of "This movie was not great."

The attention layer calculates attention scores for each token by comparing its Query vector with every preceding token's Key vector. You can think of this calculation as evaluating whether both vectors point in the same direction. This is a way of evaluating how relevant every preceding token is to each token.

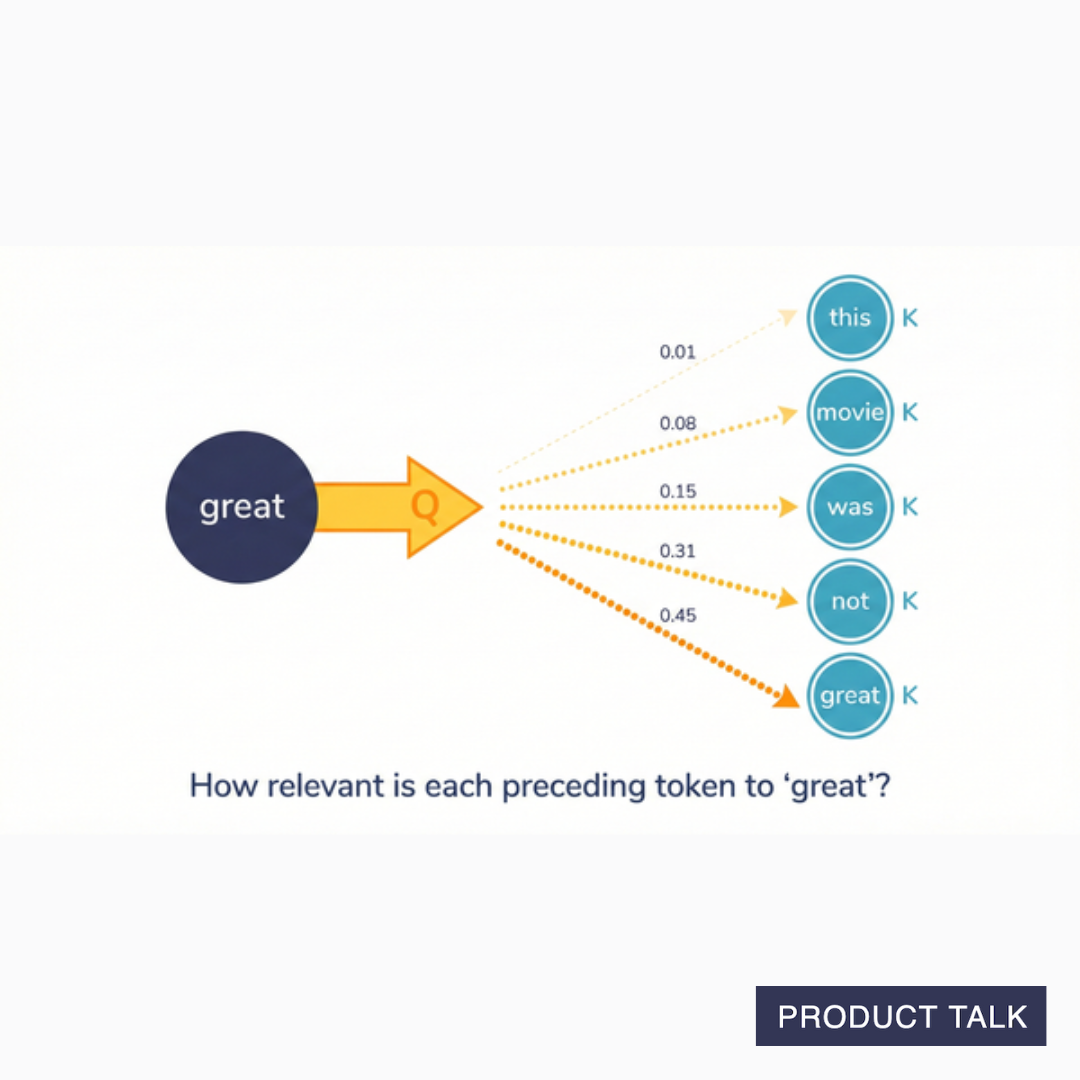

So in our movie review example, when the attention score for "great" is calculated, its great-Q is compared to this-K, movie-K, was-K, not-K, and its own great-K. The results are then normalized. That just means they are changed to percentages, so all scores add up to one. You end up with a list that represents how relevant each token is to the original token.

For example, this comparison might result in the following scores for great: (0.01, 0.08, 0.15, 0.31, 0.45). That means when understanding the relevance of each token to the meaning of "great," "this" contributes 1%, "movie" contributes 8%, "was" contributes 15%, "not" contributes 31%, and "great" contributes 45%.

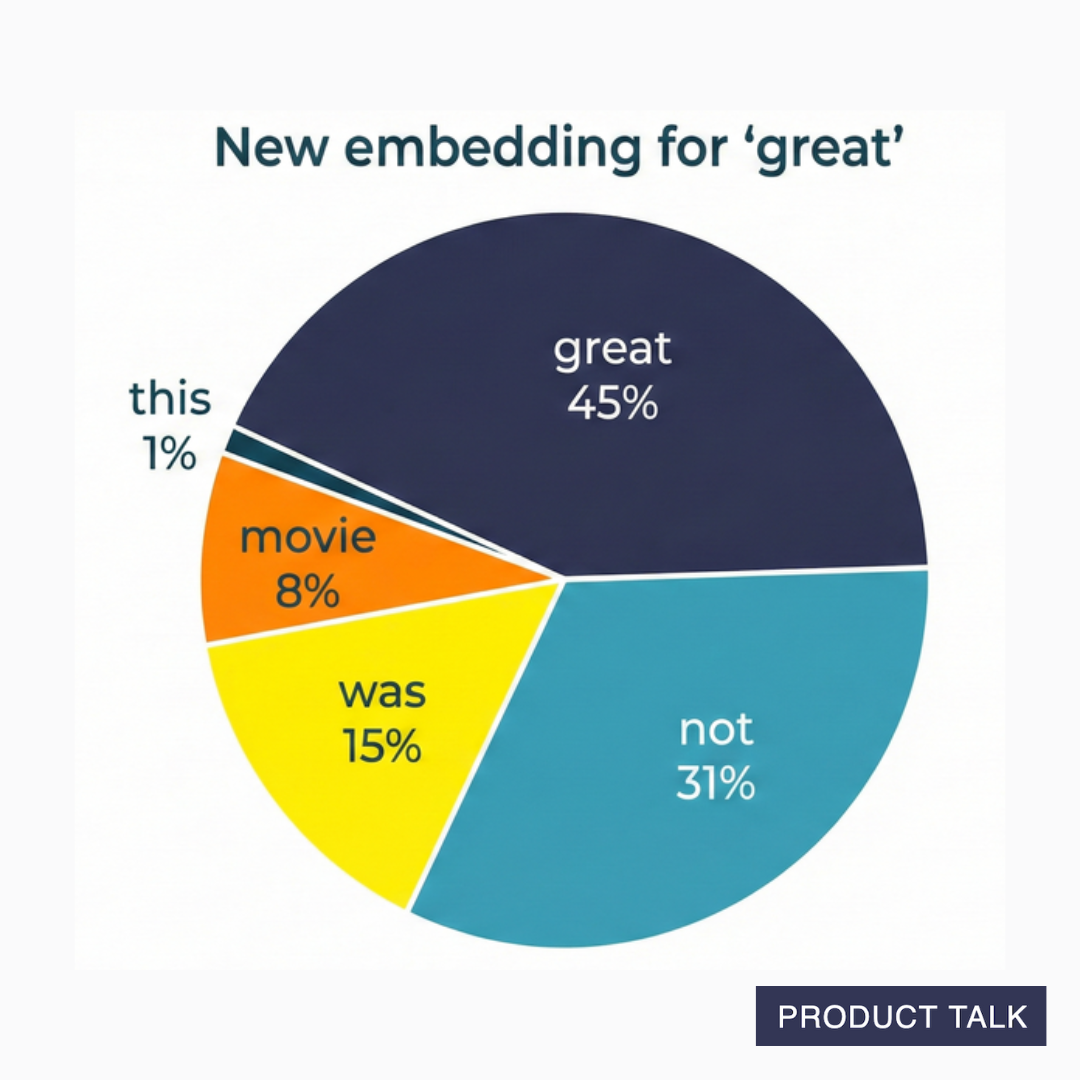

Now here's where it gets interesting and a little hard to wrap your head around. Each relevance percentage is multiplied by the V vector of the token it corresponds to. Remember, the V vector conceptually contains the content of the token. And all these multiplications are then summed. So this new value represents the content of all preceding input tokens, weighted by how relevant they are to the original token. This final value becomes the new embedding for each token.

So "great" in the context of "This movie was not great" doesn't just mean great. It actually means 1% of this, 8% of movie, 15% of was, 31% of not, and 45% of great.

When "great" gets sent along to the neural network, it is represented by this new weighted sum. The embedding captures the context in which the word appeared.

You can think about the attention layer as loading each token up with information about its context, so that when it gets to the neural network, the neural network doesn't have to look across inputs (something it can't do); it can see the full context in each individual token. That's pretty cool.

I want to take a quick aside here. I really struggled with understanding the underlying mechanism of attention. Weights are just numbers (matrices specifically) and I struggle to wrap my head around how what starts as random numbers can adopt such specific meaning through training.

How can we multiply a token embedding by a weight matrix and end up with a vector that represents anything, let alone something as specific as "what the token is looking for"? What does it even mean for a token to look for something? But the key idea here is that the math represents a way to understand the relevance between two tokens. The Q and K vectors are designed to evaluate how important another token's meaning is to its own meaning.

And just as our simple neural network learns to identify positive and negative sentiment, so too do the weights used in attention learn to do this relevance evaluation.

The Transformer Block Combines an Attention Layer with a Neural Network Layer

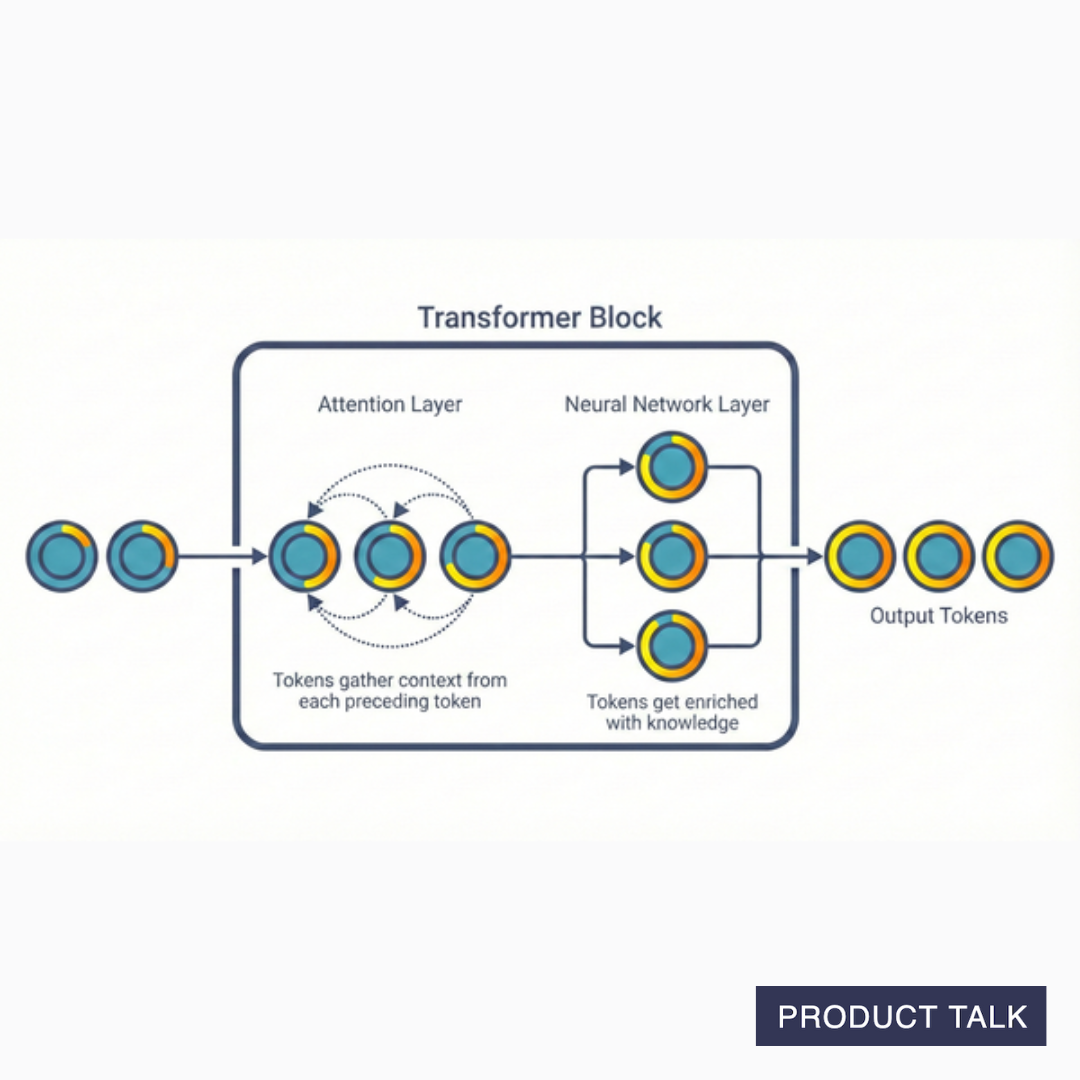

Now that we have a strong understanding of how the attention layer works and why it's important—it loads each token up with context—we can understand what a transformer actually is.

A transformer block includes two layers:

- An Attention Layer: Tokens gather context from each other

- A Neural Network Layer: Each token gets processed independently, now carrying that context

The attention layer adds context to each token in the input and the neural network layer processes those tokens. What does it mean to process those tokens? Strictly, it means in each neuron, the input token is being multiplied by its corresponding weight. But conceptually, it means the token embedding gets enriched with more meaning.

Remember, through training a neural network's weights learn how to detect different patterns. So conceptually, our "great" token might get enriched with more meaning like "this is a positive sentiment word, but in this context it's a negative sentiment word." Or it might get enriched with "great is an adjective."

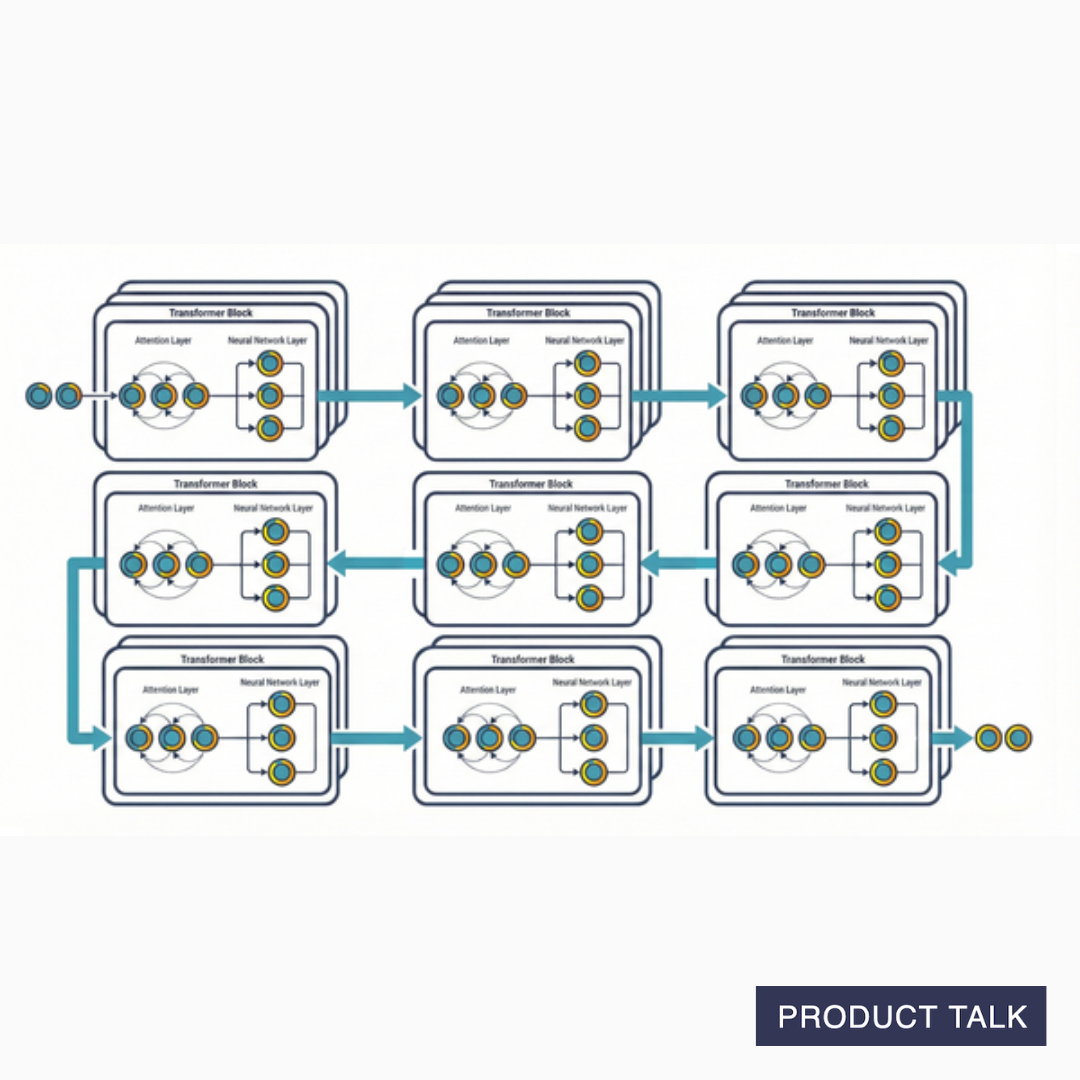

A modern model has dozens of these blocks stacked in a row. For example, GPT-3 has 96 transformer blocks. That means each token goes through this whole process—calculating attention scores and then enriching the tokens—96 times. Each layer adds more meaning.

In early layers, the model might learn basic patterns—this is a noun, that's a verb. In middle layers, more complex relationships emerge—this noun is the subject of that verb. In later layers, abstract understanding develops—this paragraph is making an argument about economics.

We don't know exactly how these patterns emerge or where specific knowledge lives. Knowledge is distributed across many neurons and connections—not neatly stored in single locations we can point to. That means we can't just look inside and see that "great is an adjective" is encoded at a specific neuron or in a specific layer. But research suggests the general picture holds: Earlier layers capture simpler patterns while later layers capture more abstract relationships.

A quick note on language: The neural network layer can also be called a feed forward layer as input only travels in one direction—it feeds forward. The input is multiplied by weights, then summed, to create the output. There are no backward moving steps. So if you hear your engineers using this term, know they are referring to the neural network layer.

We've come a long way. But there's more to go. Here's what we've learned so far. Input is tokenized and turned into embeddings. Then it's sent through the black box. The black box includes dozens (we can assume at least 96) of transformer blocks. Each block has an attention layer, where context is loaded into each token, and a neural network layer where each token is enriched with more knowledge. We now need to turn to how a prediction is made.

Part 3: The Output—Predicting the Next Token

I was surprised to learn that the model doesn't use all of the input tokens to predict the next token. It only uses the last token.

All of the input tokens are needed during the processing of the transformer blocks. They contribute context in the attention layers and they get enriched in the neural network layers. That enrichment then affects how they give context in the next attention layer. And so on.

But when it comes time to make a prediction, the model compares the last token's enriched embedding to all the embeddings in the vocabulary and asks, "What vocabulary embeddings point in the same direction?" It computes probabilities for each vocabulary token and makes a prediction.

Remember embeddings represent a point in n-dimensional space. As the token embeddings move through all the different layers of our transformer, they are getting enriched. The tip of the arrow gets nudged over and over again to point to a different location in space. It gets nudged in the attention layer based on the surrounding context of the other input tokens. And it gets nudged in the neural networks based on what it learned in training.

At the end of this process, the last token embedding has been nudged to point to a space that already accounts for all that context and learning. The earlier tokens are no longer needed. Their meaning is already embedded in the last token. The model can look at where the arrow points and make a prediction.

And here's the crazy part. Once it does that, the predicted token gets added to the input and the whole process starts again. It repeats for every token in the generated output. Wow. I hope you have a much better appreciation for what "compute" means. I know I do.

Some Final Thoughts

I want to summarize where we've been. We've learned that:

- Input is tokenized and turned into embeddings—numerical lists (vectors) that represent a point in n-dimensional space.

- Token embeddings get processed by many transformer blocks that enrich each token first with context and then knowledge.

- Each iteration nudges the vectors to point to slightly different locations.

- An output function looks at where the last vector is pointing and predicts what comes next.

I find that having a strong foundation in how large language models work helps me better understand their strengths and weaknesses. Which, in turn, helps me better understand how to use them.

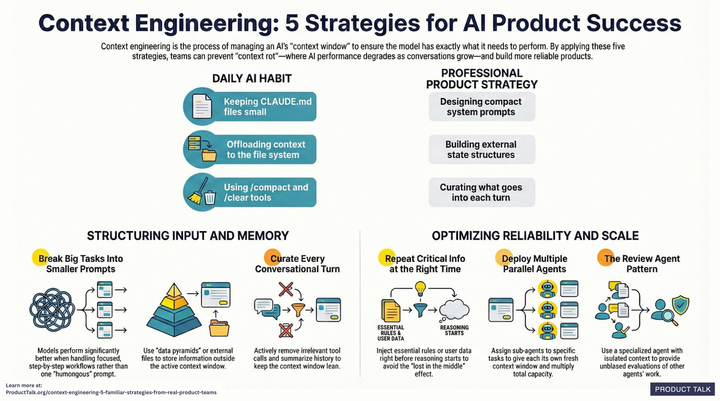

For example, I started to dive into the research on "context rot"—the idea that model performance degrades as the context window fills up. I started to wonder what context window size was a function of. I also was curious about how the different patterns that emerged in the research came about. Why would a model have a bias toward the beginning of the context vs. the end? To answer these questions, I had to dive deep into how transformers work. This article is the result.

When I started to write this article, I intended to cover more ground. I was intending to write about attention heads, KV caching, the difference between training and inference, back propagation, and much more. But 4,400 words later, I decided it was too much for one article. If like me, you find these topics fascinating and would like me to continue to demystify them, let me know in the comments.

If you are also interested in context rot and how it might impact how you should use models, stay tuned. I'll be doing a deep dive on that next.

And finally, I have to give a shout-out to Claude. I couldn't have written this article without a lot of back and forth about these ideas. I love having an infinitely patient tutor to guide me as I work through challenging concepts.

Product Talk is a reader-supported publication. If you enjoyed this article, consider subscribing.

Audio Version

The audio version is only available for paid subscribers.